Against philosophical canons: How I became a canon-shredder

Published:

Recently I published a piece in Sandra Lapointe and Erich Reck’s wonderful anthology with Routledge, Historiography and the Formation of Philosophical Canons. There I offer a conceptual analysis of philosophical canons according to which they are dogmatic practices. Then I argue that philosophical canons, so understood, undermine the ultimate practical point for which we have them, which point is to faciliate better philosophy. Even taking a very broad range of views of what counts as “better philosophy” the argument shows that philosophical canons are self-undermining because, no matter what authors, texts, and traditions they contain, they undermine the practical point for which they exist.

Now it may be that we cannot get rid of philosophical canons and still have a discipline of philosophy. Maybe disciplines, in order to exist, need a canon around which to coalesce. I don’t discuss this issue in the piece. On the other hand, if philosophical canons have this practically self-undermining feature and we can do without them, then maybe we should. Rather than conserve the philosophical canon or expand it, maybe we should shred any and all philosophical canons. This position, that we should eliminate philosophical canons, is called anti-canonism, or what I like to call being a canon-shredder.

Note that being a canon-shredder does not mean that we should shred any or all “canonical” texts. Plato and Aristotle certainly can be taught, just as Stebbing and Welby can be taught (and I do teach them all in my classes). What we shred or eliminate is not specific texts, but the dogmatic (anti-philosophical) practices which do (and must) constitute philosophical canons.

What does this mean? Dogmas are essentially theses held without the believer feeling any need to offer arguments for them. Now one can believe a dogma and philosophize about it. For example, if I believe Moses got the commandments at Sinai and deny that this view requires any rational grounding (besides revelation or faith that themselves do not require rational grounds), then my belief is a dogma. My belief is held out without inviting any kind of dialectical discussion over it. If I were to philosophize about whether faith experiences could ever give justification, then I would be philosophizing about dogmatic beliefs.

Nonetheless, if rationalization fails, my belief does not and will not waver - hence the dogmatic character of the belief. Some beliefs like dogmas are just never really on the table for being disputed (except as an exercise) or rejected. One can put on a philosopher hat, critically interrogate a religious belief, and remove the hat later. When the hat is on, they are doing philosophy. When it is off, when they again hold the belief without needing reasons for it, their stance is now dogmatic and not philosophical.

Notice also that dogmas occur in many areas of life, not just religion. In most non-philosophical disciplines, including many natural or human sciences, the existence of the external world and other minds is a dogma. It is not the sort of belief that is viewed as needing justification. It is not offered up for dialectical discussion. In the discipline of geology we do not take skeptical scenarios about the external world’s existence as up for rational debate.

In contrast, philosophers are obliged to engage in unrestricted criticism. Any and every belief is in principle up for dialectical discussion. No dogmas are allowed in philosophy. Quoting Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy:

The essential characteristic of philosophy, which makes it a study distinct from science, is criticism. It examines critically the principles employed in science and in daily life ; it searches out any inconsistencies there may be in these principles, and it only accepts them when, as the result of a critical inquiry, no reason for rejecting them has appeared.

Putting this together with the above, canons are constituted by canonizing social practices. These social practices enforce as a (dogmatic) rule that so-and-so philosopher or such-and-such text has to be studied. Much as speeding tickets are enforced dogmatically (the ticketing officer isn’t offering the citation up for debate), so is canonical status. And in my book that practices that make philosophers canonical are anti-philosophical because of their dogmatic (enforcement-like) character.

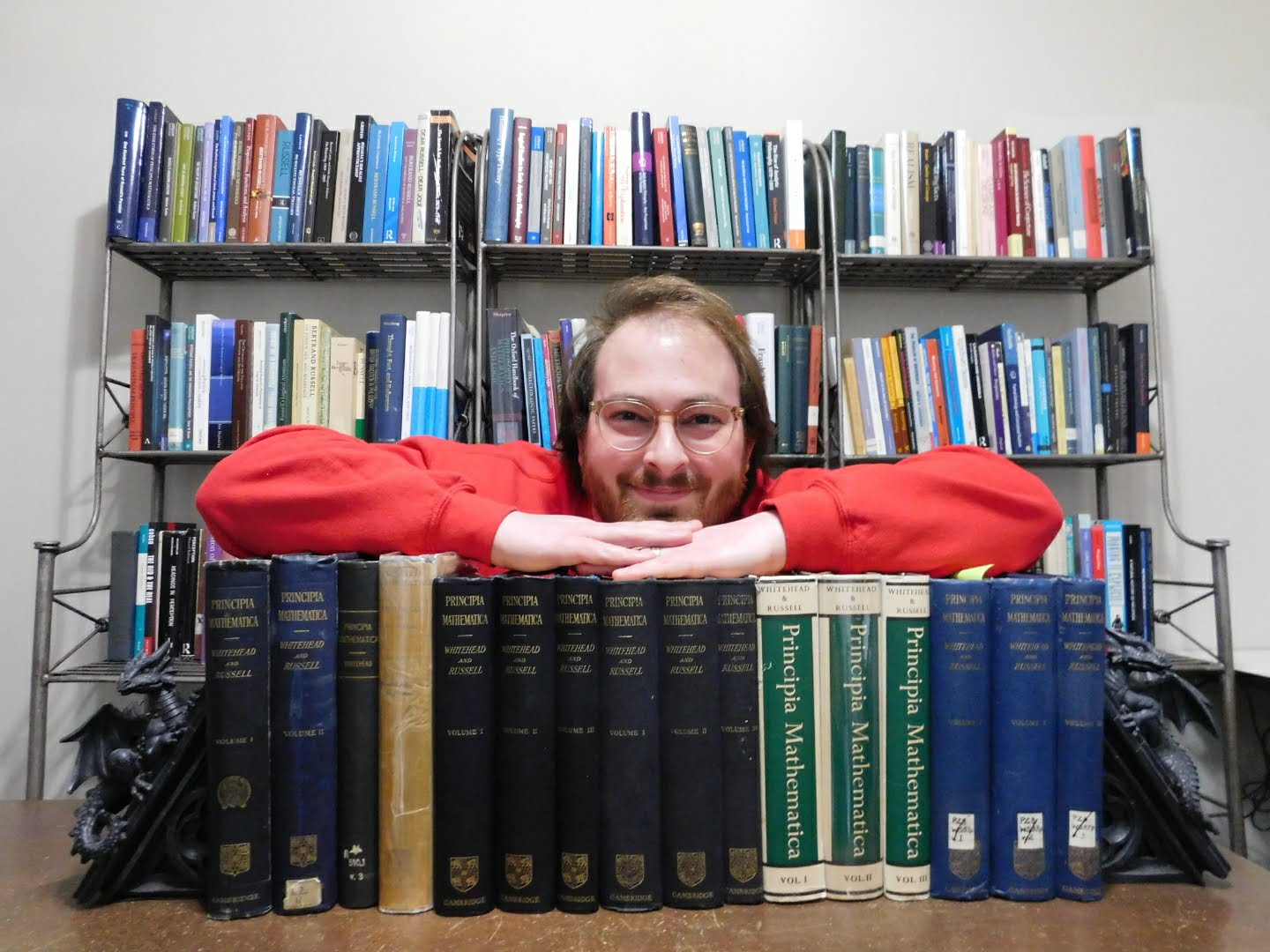

For the details, you’ll have to read the piece (and buy the book!). But how did I get to this point of thinking we should shred canons (instead of fighting over their makeup - that is, instead of either expanding them or keeping them as they are)? Basically, I kept hearing philosophers arguing that we should expand and diversify the the canon without ever bothering to say what a canon is (a good Socratic question) and what a canon is for (a good Lyndon Johnson-ian question). I got tired of not understanding the full picture about canons and what we should do with them.

This paper is the result of my bigger picture thinking about philosophical canons (and about philosophy itself, as it turns out). I hope that you that the piece or this post inspire you to do some bigger picture thinking about canons - and philoosphy, too!